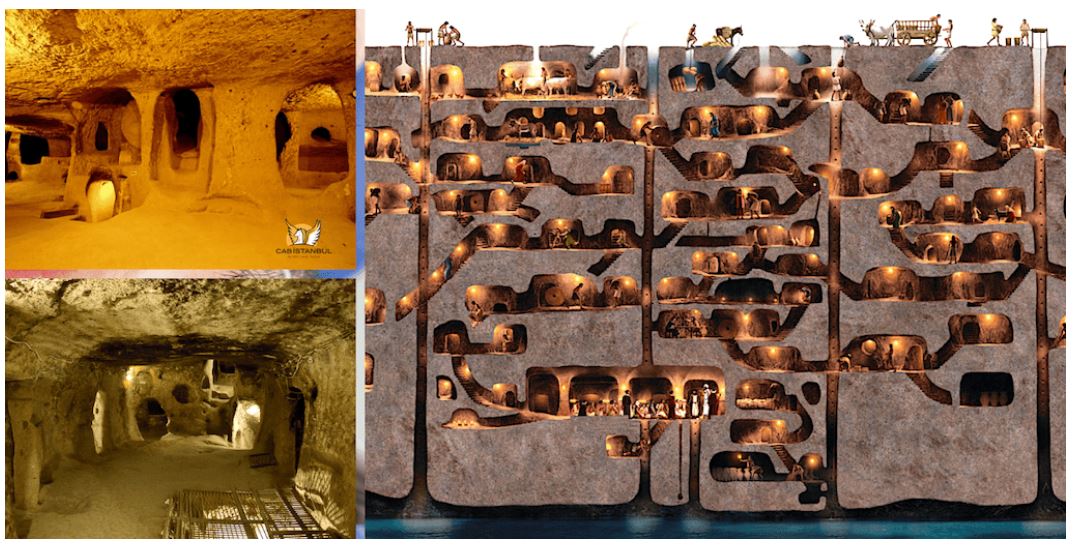

An Underground City That Defies Human Logic

In this perspective, the Kaymakli underground city in Cappadocia is not viewed as a human-built refuge, but as the infrastructure of a far older, non-human civilization, later occupied and adapted by humans. This alternative historical theory suggests that Kaymakli was originally constructed by an intelligent insectoid-like species, for whom the underground was not a place of escape, but a natural living environment.

This assumption offers a different explanation for the city’s form, scale, and internal logic, which often appear incompatible with conventional human settlement planning.

An Insectoid Civilization as Subterranean Builders

According to this theory, Kaymakli was created by a collective, colony-based species, whose social organization resembled that of ants or termites. Individual comfort held little importance; instead, the functioning of the colony as a whole was paramount.

Such a civilization would have had no need for spacious chambers or decorative architecture. Every tunnel, room, and junction would serve a biological or functional purpose, optimized for efficiency rather than aesthetics.

From this viewpoint, Kaymakli is not a city in the human sense, but a living system, where each structural element fulfills a specific role within a larger organism-like network.

Architecture Not Designed for Humans

Many of Kaymakli’s corridors are extremely narrow, with ceilings too low for prolonged upright movement. Humans must bend, crawl, or move slowly through these passages, while an insectoid-type being would find such dimensions entirely natural.

The spatial organization shows little evidence of family dwellings or individual living quarters. Instead, it suggests functional zones serving the needs of a collective entity. This architectural logic resembles biological structures rather than social settlements.

Ventilation as the “Breathing” of the Colony

One of the strongest arguments supporting this theory is the city’s highly complex ventilation shaft system. These shafts do more than supply air; they appear to regulate oxygen flow, humidity, and temperature across multiple underground levels.

For humans, such an extensive system seems excessive. For an insectoid physiology, however, maintaining a stable and controlled environment would be essential. In this interpretation, the underground complex functioned as a regulated ecosystem, not merely a shelter.

Stone Disk Doors as a Boundary Between Two Worlds

The massive circular stone doors, capable of sealing entire corridors, are not interpreted here as defenses against human invaders. Instead, they are seen as hermetic barriers separating the underground environment from the surface world.

Surface light, temperature fluctuations, and atmospheric conditions may have been biologically harmful to the insectoid inhabitants. The doors therefore served as life-preserving mechanisms, isolating the colony from external instability rather than acting as tools of warfare.

The Disappearance of the Insectoid Civilization

This theory proposes that the insectoid civilization did not vanish suddenly, but gradually declined or withdrew due to climate changes, resource depletion, or biological limitations. The underground city was left empty but structurally intact.

Its design proved so resilient that it survived for thousands of years with minimal degradation. Kaymakli thus became abandoned infrastructure, not a destroyed city.

Humans as Secondary Occupants

Within this narrative, humans arrived in Kaymakli long after the original builders were gone. Humans:

- expanded certain corridors,

- adapted chambers for daily living,

- added religious and cultural elements,

- used the city primarily as a refuge.

This explains why Kaymakli contains both human-recognizable layers and structures that feel fundamentally alien to human design principles.

Why This Theory Exists

This alternative interpretation persists because Kaymakli:

- does not appear to be designed for humans from the outset,

- is far too complex for a simple hideout,

- resembles a colony system rather than a city,

- is not fully explained by official archaeological models.

Where understanding ends, interpretation begins — and this is one of the most radical interpretations proposed.

An Unresolved Mystery

In this alternative view, Kaymakli is not a human achievement, but a remnant of an ancient, non-human intelligence that used the underground as its primary habitat. Humans later inherited and reshaped this structure for their own needs.

Even if this theory is incorrect, it highlights an essential fact: Kaymakli remains only partially understood. Its true origins, purpose, and builders continue to challenge conventional explanations.