In the 1970s, psychologist Bruce Alexander and his colleagues conducted a groundbreaking study that challenged traditional views on drug addiction. Until then, most addiction experiments had been done with rats kept alone in small metal cages. These rats were connected to devices that allowed them to self-administer drugs such as morphine or heroin. Researchers observed that the rats quickly became addicted, often choosing the drug over food or water until they died. This led many to believe that drugs themselves were so powerful that they inevitably caused addiction in anyone who used them.

However, Alexander questioned this assumption. He suggested that the rats’ behavior did not prove the irresistible nature of drugs but rather reflected their response to cruel living conditions—social isolation and an empty environment with nothing to do. To test this idea, he created two completely different settings and observed how they influenced the rats’ choices.

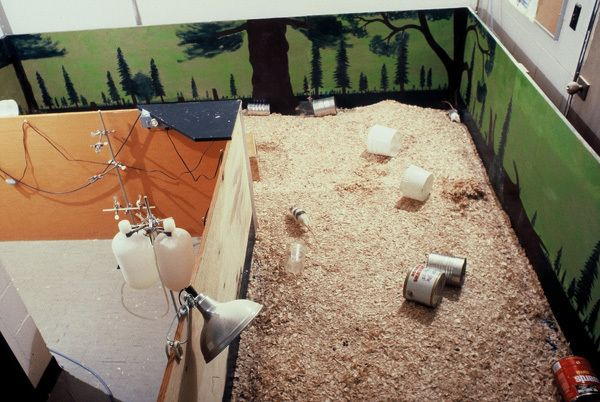

The Experimental Setup

The experiment featured two environments:

- Isolation cages – small metal cages where rats were kept alone, with no interaction, toys, or space to move. These replicated the typical conditions used in earlier addiction experiments.

- Rat Park – a large, stimulating environment filled with toys, tunnels, companions, and space to explore freely. It closely resembled a natural habitat for rats.

In both environments, rats were given a choice between:

- Plain, clean water

- Water mixed with morphine (an addictive opiate)

The goal was to see whether the environment would influence the rats’ preferences—would those living in a rich, social setting still choose drugs?

The Results

The findings were stunning and challenged the dominant beliefs about addiction:

- Rats in isolation drank large amounts of morphine water, sometimes to the point of death.

- Rats in Rat Park mostly avoided the drug-laced water. Even rats previously addicted during isolation began to prefer clean water once moved to the stimulating environment, gradually quitting the drug altogether.

These results showed that addiction is not merely a biological reaction to a substance—it is deeply shaped by environmental and social factors.

What the Experiment Reveals About Humans

Rat Park offered a new perspective on addiction in humans. If isolation and poverty promote addiction in rats, similar principles might apply to people. Real-world evidence supports this idea:

- Drug use is more common in stressful, socially isolated, and impoverished environments.

- During the Vietnam War, many soldiers used heroin, but most stopped after returning home to normal life—without medical treatment.

- Human studies show that positive relationships, safety, and purpose can reduce addiction more effectively than punishment or abstinence-based methods.

Alexander’s work demonstrated that combating addiction requires more than banning drugs—it means improving quality of life, opportunity, and community connection.

Criticism and Further Research

Although revolutionary, the Rat Park experiment has faced mixed replications. Some researchers achieved similar outcomes, while others did not. Critics argued that differences in rat species, temperament, or experimental design could affect the results.

Yet, modern studies continue to support the core insight: social and environmental factors strongly influence addiction.

For example:

- Research on childhood trauma shows that emotional or physical abuse significantly raises the risk of substance abuse later in life.

- Neuroscience studies reveal that loneliness alters the brain’s reward system, making individuals more vulnerable to addictive behaviors.

Key Takeaways

- Environment and social connection play a crucial role in addiction.

- Isolation, stress, and deprivation increase addiction risk, while engaging, supportive environments reduce it.

- Effective addiction prevention must address social and economic well-being, not just drug availability.

Conclusion

The Rat Park experiment revolutionized our understanding of addiction. It proved that drug dependence is not simply a matter of chemistry—it’s also a reflection of how we live, connect, and find meaning. Instead of asking “Why the addiction?”, Bruce Alexander’s work encourages us to ask a deeper question:

“Why the pain?”